History of Potteric Carr

This section covers the history of a large area of low-lying land to the south-east of Doncaster known as Potteric Carr of which Potteric Carr Nature Reserve is but a small part. It describes the changing land uses, particularly in the last 400 years, how these have influenced the area and how they, ultimately, led to the creation of Potteric Carr Nature Reserve.

Early history from Roman times to 1840

At the time of the Roman occupation much of lowland Britain was either thickly wooded or marshland. Most of the land to the east of Doncaster is only a few metres above sea level and consequently would at that time have comprised a vast marshy area. There is evidence that the Romans made some attempts at drainage but their work fell into disrepair on their departure from Britain.

Little is known of the next thousand years but one of the earliest references to Potteric Carr comes from the itinerary of Leland circa 1540:– “Before I came to the town, I passed the ford of a brooke, which, as I remember is called Rossington Bridge... The soil about Doncaster hath very good meadow, corn and some wood.”

As Leland travelled into Doncaster from Bawtry, he passed through a landscape unfamiliar to us today. Sherwood Forest then extended to the boundaries of Doncaster and venerable oaks dotted the landscape from Bawtry to Hatfield. To the west of the road from Rossington Bridge into Doncaster, Leland passed the “largely impenetrable morass of bog and fen known locally as Potteric Carr”. Earlier he would have caught glimpses in the east of a similar wild tract of marshy country which then covered the whole of the flat land between the rivers Don and the Trent.

By the time of King Henry VIII, Potteric Carr was a small part of Hatfield Chase, the largest deer chase in the realm. The chase eventually fell from royal favour about the time of the reign of Elizabeth I, due to its permanently inundated state.

Social and geographical changes (1600—1840)

Over the next 150 years a number of largely unsuccessful attempts at draining the Carr were made to make the land suitable for farming. One of the earliest attempts was made around 1630 by Cornelius Vermuyden who was also noted for his drainage schemes in the English fens. In 1657 Doncaster Duck Decoy was established just 700m northwest of where Decoy Marsh is today. Duck decoys were perfected in Holland and were a method of catching wild ducks. The idea may have been introduced to the area by Dutch workers who came to Britain with Vermuyden. The Decoy was operated for about 130 years during which time the proceeds from the Decoy were distributed amongst the poor of Doncaster. However, its closure was foreshadowed in the 1760s when a civil engineer, John Smeaton, carried out the final and most effective drainage scheme so that by the end of the century much of the area was under agriculture. So successful was the drainage that the only remnant of the original flora was probably confined to a small area in and around the Decoy which was by then disused.

In the first half of the 19th century a number of afforestation schemes were carried out with plantations at Beeston, Old Eaa, Young Eaa, Black Carr and Stoven’s and many hedges were planted. The plantations which were mostly of Oak Quercus robur , were intended to replenish timber stocks, large quantities of which had been depleted by the Napoleonic Wars. The development of iron and steel ships meant that they were no longer needed.

Thus by the middle of the 19th century the landscape was probably typical of an English rural scene with farmers’ fields, hedges, trees and larger tracts of woodland all effectively being maintained by the efficiency of the drains. The great industrial era was just around the corner, however, and the next 100 years would see further remarkable changes to the area.

Industrial development (1840—1950)

In 1849 the Great Northern Railway was built across the Carr cutting through the Old Eaa Plantation and the centre of the Decoy totally destroying in the process the last refuge of many scarce plants. The construction of this railway was the beginning of an era in Doncaster (see Railways page) which was for many years a major railway centre. With the railways came workshops and new residential development was required to house the employees of the railway works. Hence rows of inexpensive houses were erected around the periphery of the town particularly in the Wheatley and Hexthorpe areas.

The railway was a lifeline for another new industry — the coal industry — which was rapidly eclipsing the agriculture which had dominated the area in the 18th century. Both industries were hungry for land and in 1862 the Great Northern Railway Company purchased 16 ha between the Doncaster—Sheffield road and the Decoy for the construction of a marshalling yard for coal traffic. The work was completed in 1866 and the sidings ended at about the centre of the Decoy. At the same time the Lincoln branch line was being constructed and this cut through Stoven’s Plantation just as the main line had done in 1849.

In the ensuing years, Doncaster expanded considerably particularly after deep coal seams were found in the district and, in conjunction with this, there was a further expansion of the railway system. Around 1880 the extension of the decoy sidings completely destroyed Decoy Wood and, at the turn of the century, the construction of the Dearne Valley Railway sliced another piece of land from the Carr.

In 1908 the South Yorkshire Joint Railway was constructed which ran to Maltby and Dinnington in the south. Where this line crossed the East Coast Main Line (London—Edinburgh), loop lines were constructed to link the north and south sides of the Decoy Sidings and also the Dearne Valley Railway.

Within the next 20 years several local collieries were opened commencing with Maltby in 1910 and Rossington in 1915, and this resulted in a considerable amount of railway activity in the area, particularly in the inter-war period. Certain link lines were never fully utilised however and, following the post war decline in rail freight traffic, some of the lines on the Carr became disused. It is paradoxical that at a time of increasing land values these lines became derelict and, more importantly, so did several parcels of land sandwiched between the railways – land which was obviously not an economical proposition for the farmer. Willow Triangle was one such area and it rapidly became dense willow carr.

Clearly this industrial period, which brought so much activity in the early part of the 20th century, considerably fragmented the area though most of the wildlife for which the Carr was once famous had long since gone.

1950—68

After having survived the effects of various drainage schemes, considerable agricultural activity and also industrial expansion, Potteric Carr was to endure yet another development which was to have a tremendous effect on the area.

In 1951 an underground seam from Rossington Colliery undermined the area of Low Ellers. This was followed by further seams which affected the whole of the Carr between 1960 and 1967. The effects were not immediate. In 1955, the area of Low Ellers was no more than a damp pasture and, even by 1959, was only slightly wetter.

Low Ellers 1960 © Roger Mitchell

Low Ellers 1977 © John Hancox

From this time onwards, however, the effects of subsidence became more severe and by 1963, Low Ellers had been transformed into marsh with a small but permanent area of open water. The farmer’s field immediately to the east of Low Ellers Curve had also become flooded — one species benefiting here being breeding Garganey!

The subsidence continued and by 1965 Balby Carr including Young Eaa Wood had also flooded as had Corbett Wood, whilst the marsh at Low Ellers had extended with more open water and an area of reed fen. Parts of the area had started to resemble its state 200 years earlier. Those areas which had not become completely flooded were at least very wet. One loss during this period was the trees in the Young Eaa Plantation, which by that time included many Silver Birch along with Oak, and a part of the Old Eaa Plantation, mainly Oak, which died as a consequence of the flooding. There followed, however, a very fast colonisation of the area by marsh plant communities which once typified the Carr and naturally, following this, the return of the animal life.

Balby Carr / Young Eaa Plantation 1974 © John Hancox

Key events in the history of Potteric Carr Nature Reserve 1968—2005

This relatively small area of land on the outskirts of Doncaster was in 1968 largely surrounded by open country. As the events below reveal, everyone apparently had plans for this land for various uses but, under the leadership of Roger Mitchell, assisted by hundreds of volunteers, the Reserve flourished and grew often against the odds.

1968

The protection and development of the Reserve commenced in 1968 with the tenancy of 13 ha of marsh at Low Ellers from British Rail. With strong support from the Chief Executive Officer of Yorkshire Wildlife Trust, Lt Col John Newman, a Management Committee (RMC) was formed to run the Reserve. This comprised local volunteers led by Roger Mitchell. During the next 20 years, visitors to the site had to be in possession of a railway walking permit of which initially only a few were issued. This gradually increased to 200 covering a two-year period including a small number which permitted the holder and ten others accompanying him/her.

It was recognised that nature conservation as well as being about wildlife is also about people and there was a burgeoning interest in wildlife at this time, largely as a result of activities by RSPB and an increase in birdwatching, and in 1970, European Conservation Year. The RMC regularly held “open days” when local communities could visit the Potteric Carr and be shown round by wardens. As well as increasing awareness of the Reserve activities, it also attracted people to the YWT and raised funds for the nature reserve.

1971

YWT supported Doncaster Council in opposing the proposed “inner route” for the M18 motorway preferring the outer route (as eventually built). This was probably the first time that nature conservation and wider conservation issues played a major part in the Secretary of State agreeing to reject a motorway proposal and to seek an environmentally less damaging route.

1973

The track and signals, etc., from the railways that had become redundant as a result of the Dr Beeching Report were removed.

Loversall Bank 1970 © Roger Mitchell

Loversall Bank 1984 © John Hancox

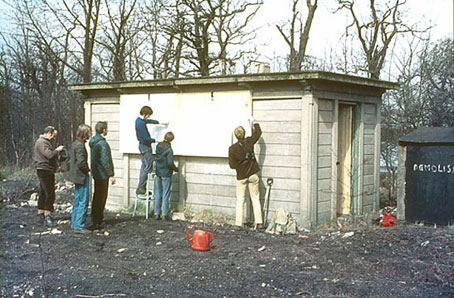

A small concrete line shack was left as a base for volunteers on site. This was refurbished and made into a small Field Station for recording work, storage of equipment and so on.

Old line side shack being converted into a field station in 1973, with George Richardson (far left), Roger Mitchell (on chair) and Brian Leflay (far right) © Roger Mitchell

On completion, volunteers fenced off the northern half of the Loversall Bank to allow the regeneration of trees.

By agreement with British Rail, during the next few months, volunteers assiduously collected material left by the removal contractors – rail chairs, keys, old sleepers, bolts and more. The metals were sold to a local scrap dealer for cash for the Reserve and raised over £1,000 (over £9,000 at 2012 prices!). The sleepers were used as bases for hides, bridges and steps — improvisation was important!

Sleepers and rail fishplates used to fashion steps © John Hancox

With the loan of a small prototype bulldozer by International Harvester, volunteers created a small pool at Willow Triangle (opposite the Field Station) together with a small hide and access bridge from Loversall Bank.

1974—76

Using the same bulldozer, work started by volunteers to create a new wetland on a former rough pasture immediately to the east of Black Carr Wood.

Scraping Piper Marsh; Mike Bellas driving; 1974

© Roger Mitchell

Roger Mitchell on bulldozer loaned by International Harvester; Harry Whalley (left) and Mike Bellas watch © Roger Mitchell

This area was called Piper Marsh after a sandpiper was heard calling over the area during the scraping work. Whilst a small water body was created, however, it was clear that this small machine and a few volunteers weren’t up to the task of scraping the whole area and assistance was obtained from the contractors for the new railway works. Some areas of open water were created but the arisings left large unsightly mounds of spoil before rain intervened and ended operations. It was to be another 15 years before the work was finally completed.

Piper Marsh 1977 showing heaps of spoil left by marsh creation © John Hancox

1975

By this time, further parcels of land, much of it between railway lines, had been acquired increasing the area to over 100 ha. As well as increasing the landholding, it was also a hedge against possible loss of land due to the M18 extension. A small grant was obtained to enable the employment of a part-time warden (shared with Denaby Ings Nature Reserve). This was taken up by a retired person and, despite it being for only 2–3 days per week, such was his enthusiasm that he was on site most of the time. The RMC and British Rail worked closely together with great success to limit the damage to the Reserve by the changes to the railway infrastructure on the Reserve to accommodate the new High Speed Trains on the East Coast Main Line in 1977. The work was carried out in 1975/6. The agreement with British Rail involved several innovative approaches which were widely seen as a model of consultation and compromise between the voluntary sector and a developer.

Railway construction 1976 - Ian Heppenstall on right © John Hancox

1977

A larger part of the Reserve was designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) primarily to protect the extensive areas of reed fen and the wildlife communities associated with them.

The Reserve was proposed as a water balancing area for the storage of surface water from south Doncaster. This could have resulted in the destruction of all the wetlands on the Reserve but, in what was probably a unique compromise agreement between the YWT and the Potteric Carr Internal Drainage Board (PCIDB), most of the wetlands were allowed to remain. Although there was ecological loss, primarily the lowering of the water table of Loversall Pool (4 ha) and Willow Triangle (12 ha) and over 25 ha of pasture within and to the west and north of the Reserve, the agreement was widely acclaimed for its success in addressing potentially conflicting engineering and ecological requirements. The works commenced in 1980 and involved the deepening and regrading of the major drains on the site, the building of two pumping stations and a new field drain between Childers Drain in Hawthorn Field and Piper Marsh which involved the removal and reinstatement of Hawthorn Bank. The scheme was implemented in 1981. Also included in the works was the construction of an access track to the pumping station on Loversall Bank near the centre of the Reserve operations. This was the first time the Reserve had had a proper vehicular access.

Drainage scheme - regrading Mother Drain 1980 © John Hancox

Drainage scheme - new drain in Black Carr Field 1980 © John Hancox

1979

Volunteers dismantled the signal box at Low Ellers which, with the new signalling system, had become redundant. One of the sign-boards is now displayed in the present Field Centre café.

Volunteers dismantling signal box © John Hancox

1980

A new hide was built overlooking Low Ellers Marsh with access across the new lighted crossing over Decoy Bank.

Low Ellers (Childers Wood) Hide 1980 © John Hancox

1981

The construction of a Field Centre at the centre of the Reserve was completed. This was funded through government training schemes. It was initially used as a storage location and display area but later became the hub of the Reserve for wardens, volunteers and the general public.

1981—90

Following completion of the water balancing scheme, which had created enormous disturbance throughout the Reserve during its construction stage, YWT embarked on a major scheme to heal the scars of development, undertake extensive habitat management and greatly improve access and visitor facilities.

Boardwalk through Corbett Wood 1986 © John Hancox

The freehold of 3 ha of the Reserve, hitherto leased, was acquired in 1987. During this period the number of visitors to the Reserve rose dramatically as the Reserve became better known amongst local communities. The Reserve was renotified by Natural England (formerly English Nature) under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

1984

A pair of Little Bittern

Oxyura jamaicencis

bred successfully on Low Ellers Marsh, raising three young. This was the only record of successful breeding in Britain until 2010, when a pair bred in south-west England. Thousands of visitors came from all over the UK to witness this famous Potteric Carr occurrence.

Little Bittern (male) © Jamie McArthur

1985

Sir David Attenborough, on his first visit to Potteric Carr, opened a new viewing hide overlooking the developing wetland at Piper Marsh. Shallow excavations, funded by the sale of the topsoil, provided a new 6 ha wetland at no cost to YWT and the work was completed in 1990. As a part of the scheme, the delivery of water by gravity from Low Ellers provided the means to re-establish a high water table in this area following the effects of the water balancing scheme.

Sir David Attenborough

opening Piper Marsh hide © John Hancox

1986

A modest extension to the programme of school visits, based on the new Field Centre, was implemented. This was facilitated by the involvement of several new “early retired” volunteers.

1987

The Reserve’s own pumping scheme was commissioned providing the capability to pump water into Loversall Pool and Willow Triangle primarily from Division Drain but also Mother Drain to maintain water levels which had been greatly reduced by the water balancing scheme completed in 1981.

Volunteers working on Potteric Carr pumping scheme © John Hancox

1988

With the establishment of new storage units near the Field Centre, which had been provided free of charge by Central Electicity Generating Board, the use of the Field Centre was changed to create a café, staffed by volunteers. This started in a small way providing hot drinks for working volunteers but quickly expanded into hot drinks and food and then a small café. The café was built by volunteers from second-hand units. (It should be noted that, at this time, although there was electricity to the Field Centre, there was no water service and this had to be brought in by hand in 10 litre containers. It was to be some years before a water supply was installed by volunteers serviced from an old feed to a water trough in Adam’s Field!) The café was popular with wardens, volunteers and visitors alike and became the “social hub” of the Reserve operation. It enabled an extension of Reserve’s social activities including an extensive programme of events (birdwatching, botany, photography and other courses), a base from where field studies/recording could take place and an increase in organised working groups with a new Tuesday group (previously such work had only operated on Sundays). The Field Centre was open on Sundays and Tuesdays and it was to have a marked influence on the Reserve operation and visitor profile over the next 16 years.

1989

With a grant from the British Rail Community Unit, a part-time Maintenance Officer was employed. This was later increased to full time and when the grant ceased the cost was borne by YWT core funding. Internationally renowned Professor Chris Baines described Potteric Carr Nature Reserve as one of the most important of its type in Europe. The Potteric Carr WATCH Group (junior section) was launched. Run entirely by volunteers, the Group operated a programme of monthly events. It eventually became the Family Group, and operated under this name until 2003.

1993

The hides on the Reserve began to be used by juveniles at night and evidence of drugs was found. In April, three important viewing hides at Black Carr Wood, Old Eaa and Childers were burnt down.

Remains of Low Ellers Hide following arson © John Hancox

A major fund raising initiative was launched and two of the hides, Old Eaa and Childers were rebuilt in red brick at a cost of £20,000. This was the only major act of vandalism suffered by the Reserve since its establishment.

On August 3rd, Sir David Attenborough, on his second visit, addressed over 300 invited guests on the 25th Anniversary of the Reserve’s establishment. Amongst the guests were Lord Scarbrough, representatives of English Nature (Natural England), RSPB, The Wildlife Trusts and the Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council. The event was videoed for posterity! Speaking during a full day of activities on the Reserve, when Sir David toured round and met many of the active volunteers, he applauded the past efforts of the public, private and voluntary sectors in working together to make Potteric Carr such a success. He expressed apprehension about the effect which new developments around the Reserve would have but was optimistic that if the willingness in the past of all parties to work together was displayed in the future, the Reserve would flourish.

Ann Bacon and Maureen Hancox in the original cafe 1993 © Allan Parker ARPS

Left, David Attenborough with the ladies from the cafe, left-right: Jennifer Lowe, Beryl Drabble, Maureen Hancox, Diane Scarfe and right, David Attenborough with Dorothy Bramley

both images © Allan Parker ARPS

1994

In June, Doncaster MBC produced their Unitary Development Plan (UDP) – Deposit Draft. This included the allocation of approximately 1500 ha of land around the Reserve, for development purposes. Three major Mixed Use Regeneration Projects were identified – Woodfield Plantation, Rossington Hall and Doncaster Leisure Park/Doncaster Carr; also a large housing development at Manor Farm. Over 400 ha of this land was already under development or had the benefit of planning permissions. The effect on Potteric Carr by virtue of loss of habitat, surface water run-off and pressure of visitors would clearly be enormous. A new Management Plan was adopted for the Reserve.

1995

In Willow Marsh, following the removal of trees during the previous two winters by a team of volunteers, work was carried out to extend the water body at Willow Pool and create an area of reed fen to a design by RSPB. Two new hides sponsored by Royal Mail and CEGB were built overlooking the area.

Willow Marsh Excavations © John Hancox

1996

YWT examined the future prospects of the Reserve against the proposals for the development of surrounding land and produced a plan for the future in four phases which was eventually approved by YWT Council. An agreement with Moorfield Developments Yorkshire was reached for the assignment to the YWT of an option to purchase 75 ha of land to the south of the Reserve.

1997

Following a Public Inquiry, the Inspector’s Report on the Doncaster UDP confirmed the development proposals for Woodfield Plantation, Doncaster Carr/Leisure Park and Manor Farm, with minor modifications. The Rossington Hall development proposal, south of the M18 motorway, was rejected. The Reserve would now be faced with around 700 ha of development on its western, northern and eastern boundaries.

Field Centre area 1997 © John Hancox

1998

Phase I of the Potteric Carr Development Scheme was completed. This involved primarily the creation of Decoy Lake and the Reed Bed Filtration system, and the upgrading of the access track with a tarmacked surface.

Reed Bed Filtration System – Cell C © John Hancox

In October, Doncaster MBC first attached a condition to a planning application for development on land surrounding the Reserve. This condition has been attached to all subsequent applications where appropriate.

1999

The RMC commenced work on the detailed planning and feasibility for Phase II of the Development Project. A small Development Committee comprising local volunteers and YWT Trustees was set up chaired by Lord Peel.

2000

A new option to purchase the 75 ha of land to the south of the Reserve was signed directly between the YWT and the vendor, replacing the previous option arranged through Moorfield Developments. In March, a grant application was made to the Heritage Lottery Fund and approaches made regarding matching funding for Phase II of the Development Scheme which included a new Field Centre, upgrading of paths to make them suitable for wheelchairs, a modernisation of the maintenance area with powered equipment, and various habitat works.

In June, the Development and Transport Board of Doncaster MBC approved a Special Planning Guidance report setting out a methodology for “compensation and mitigation measures required in the case of developments affecting nature conservation sites”. In approving the report, the Board approved that the methodology be used for development control purposes with immediate effect.

2001

The development of plans for the refurbishment of the Reserve entrance area including an Environment Centre for Doncaster in partnership with British Trust for Conservation Volunteers, Groundwork and Doncaster MBC. This subsequently became Sedum House, the headquarters of BTCV; part of it is now the entrance offices for Potteric Carr Nature Reserve, housing YWT staff.

In May, the YWT was invited by the RSPB to join in a bid for the EU LIFE — Nature Programme fund for the purchase and development of the infrastructure on 58 ha of land to the south (part of the 75 ha extension land) as a reed bed habitat for Bitterns involving the acquisition and stage 1 development. A further stage of development, not within the funding provided by the EU LIFE — Nature bid, would follow once funding was secured. In September 2001 a revised grant application was submitted to Heritage Lottery Fund for the Phase II developments. In parallel, YWT pursued matching funding from a variety of sources.

2002

In March, HLF informed YWT that a stage 1 pass had been approved for the Potteric Carr development proposals and development costs awarded to allow YWT to proceed to stage 2. In parallel, informal approval, subject to confirmation in May, was received from the European Union for the EU LIFE — Nature Programme bid.

Overhead view in 2004 looking NW: shows the proximity of the developments; in the foreground is Willow Marsh with its reed bed system and bottom right is the former field which is now Huxter Well Marsh – the very old field drain is clearly shown in the crop

2004

Work began on site on Phases II and III of the Potteric Carr NR Development Scheme. This website was created by friends of Potteric Carr. A seven year study on the breeding birds of Huxter Well Marsh began.

2005

Phase II was completed and a staff team from the YWT took over the day-to-day operation of the Reserve. Work continued on Phase III as funding continued to be sought as the work progressed. It was successfully completed in 2008. Phase IV of the development is still in abeyance.

Thus ended an extremely successful 37 years of operation of the Reserve by local volunteers headed by Roger Mitchell MBE. The many thousands of hours by volunteers had brought the Potteric Carr NR to a point where its development into a 203 ha (500 acres) flagship wildlife site of the YWT had been made possible. Without the continued dedication of many volunteers it is doubtful that the Reserve would have survived!

text © J Hancox and R D Mitchell