The Doncaster duck decoy at Potteric Carr

Visitors to Potteric Carr will see that quite a number of sites within the Reserve have the name “decoy” in them. This is because part of the site of what is now Potteric Carr Nature Reserve, at its western end, and extending onto the industrial sites on Carr Hill, there was a decoy that operated for over 100 years with the income going to the poor of Doncaster. The following is a brief history of decoys in Britain, including the one at Potteric Carr.

The problem with ducks is that, if you want to catch them, they fly away! In the past many methods have been used to catch them mainly for food. One method, which has been in use for at least 1,000 years, was to use the fact that ducks are flightless for a short period during moult and during this time they were driven into nets or traps. Another more savage method, mainly used in Norfolk, was the “punt gun”. This used the element of stealth using a shallow punt to approach a flock of ducks with the fowler in the punt maintaining a low profile and discharging the gun at the last moment. This could bring down a large number of ducks but would probably leave some to get away even though badly injured.

In the 16th century, a new method was introduced into this country by the Dutch which had the advantage of enticing fully winged ducks into a trap. In fact the word decoy is a corruption of the Dutch word ‘eendenkooi’ meaning duck cage or trap. Potteric Carr was famous for its Decoy which was one of the first to be built in Britain in around 1657. It was set up thanks to a charitable trust and was leased out by Doncaster Corporation. The income from the Decoy was spent on the poor of Doncaster.

The Doncaster Decoy was a circular pool covering nearly 3 ha. (around 7 acres or more accurately 6 acres, 3 rods, 27 poles). In 1866, C. W. Hatfield, a local historian, wrote that around the lake was a grass walk on a raised embankment which was hidden from the lake by a screen of matted hurdles. Around the whole Decoy, alders and willows grew, hiding it from the rest of the Carr and providing a peaceful refuge where wildfowl could settle, apparently in complete safety. The technique was to include amongst the wild ducks a number of decoys, i.e. ducks that had been pinioned preventing them from flying. The tame ducks learnt to come for food when the fowler whistled softly to them and it was these that attracted other ducks to join them on the Decoy.

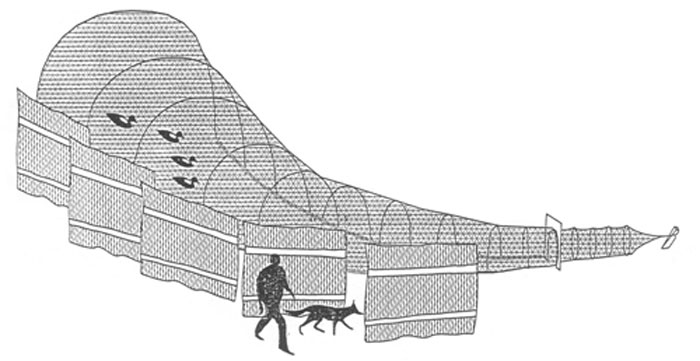

Radiating from the lake was a series of six channels or pipes covered in netting (the illustration shows a typical pipe). When the fowler thought there were enough ducks on the decoy lake, he would whistle quietly to attract the tame ducks down one of the pipes, where he regularly fed them, and the noise attracted the wild ducks to join them for the feast! Once there were plenty of ducks in the pipe, the fowler would reveal himself at the entrance of the pipe driving the ducks further down the channel trapping them in the net at the end from where they were removed.

Information about a similar decoy at Slimbridge in Gloucestershire (Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust), where one still exists, provides a clearer description. In this case, six channels led from the lake, each channel covered by a net starting about 2.7 m (9 ft.) wide and gradually narrowed forming a funnel about 12 m (40 ft.) long curving in a sort of “L” shape. The ducks were enticed along the pipe by exploiting their natural reaction to a predator. If ducks on a pond spot a fox prowling on the bank, rather than fleeing from it, surprisingly, they swim towards it, maintaining a safe distance but keeping the fox in sight similar to the way birds will “mob” a predatory cat in your garden. The decoyman used a dog to achieve the same response. The decoy pipe had a series of reed screens which prevented the decoyman from being seen by the ducks, but the dog popped out between the screens one after the other leading the ducks further up the pipe where they were caught as described above.

At the Doncaster Decoy, ducks were not taken during the breeding season and trapping took place from November to March when, as now, the resident ducks would be joined by large numbers of migrant ducks from the continent wintering in our somewhat milder climate. This meant that there was a rich harvest over Christmas!

There were about 250 decoys in Britain during their heyday between 1750 and 1850 but they gradually disappeared as the crop became less lucrative and by 1900 few were left. The Doncaster Decoy at Potteric Carr was first leased in 1662 and passed through several hands over the years. From 1728 it was leased by Viscount Galway and the Marquis of Granby but when Viscount Galway died in 1751, interest grew in draining the Carr. Once this was completed in around 1771, the end of the Decoy was in sight, although it was still there in 1778. In 1805, the Decoy was planted with trees but later the Great Northern Railway, constructed in the 1840s, passed through the centre of it and later most of the site was covered with railways sidings (called appropriately enough Decoy Sidings) and other buildings.

The present nature reserve encompasses at least some of the site of the woodlands around the old Decoy, primarily the section which has been named Decoy Marsh, but the Decoy itself was just to the west of the present A6182 (M18 link road) partly on the site of what is now a manufacturing company The remains of dead trees in Decoy Marsh are almost certainly the last remnants of those planted in 1805.

Duck decoys are now largely a part of history though one or two still exist, as at Slimbridge, mainly for the interest of visitors. It would be interesting to build one at Potteric Carr, although it would take up far too much space, but at some time it may be possible to build a model of one to demonstrate how it worked. Interestingly, a similar arrangement has been used in recent years at a number of sites in Britain for trapping birds for ringing – it is known as a ‘Heligoland trap’.

We are indebted to Mr. G. Bennett for some of the historical data in this article, which is adapted from one that appeared in the

Bessacarr and Cantley Times.

© John Hancox